بررسی ِ جهش ِ فرهنگی ِ مردم ِ ایران

سخنرانی ارائه شده در انجمن فرهنگ ایران پاریس ۲۰۰۸

فرهنگ و هنر

راديو فردا

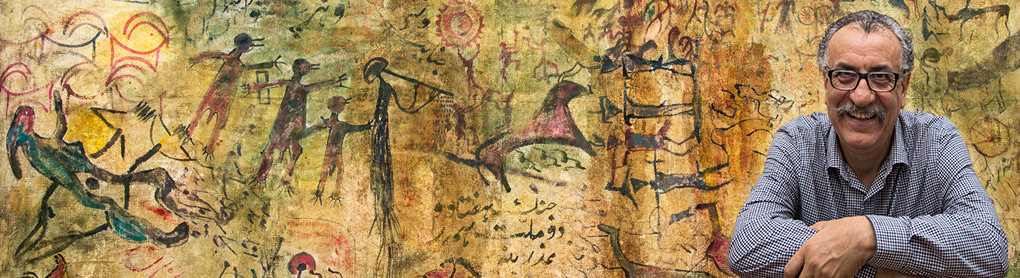

سخنرانی حسن مکارمی در انجمن فرهنگ ایران در پاریس درباره سنت و مدرنیته

ز عمر برخورد آنکس که در همه کاری نخست بنگرد، آنگه طریق آن گیرد

(حافظ : قصیده شمارۀ ٣)

متن سخنرانی : نگاهی به اهداف اساسی تجدد خواهی در ایران در دو قرن گذشته (طرح مطالعاتی در قالب مرکز مطالعات دیپلماسی و استراتژی – پاریس) این سخنرانی در چهارم آوریل ٢٠٠٨، از طرف انجمن فرهنگ ایران در مرکز آندره مالرو پاریس برگزار گردید.

ز عمر برخورد آنکس که در همه کاری نخست بنگرد، آنگه طریق آن گیرد

(حافظ : قصیده شمارۀ ٣)

- در گفتگوئی با یکی از پژوهشگران تاریخ سیاسی – اجتماعی دوران معاصر ایران، وقتی در مورد منابعی که بتوان در مورد اهداف اساسی تجدد در ایران از آنها استفاده کرد سخن گفتم، در پاسخ گفت:

"نه بابا این حرفها کدام است، چون کشاورزی ما که دیمی بوده است، همه کارِ ما دیمی بوده است ... اهداف اساسی ..."

١ـ خلاصه رسمی طرح مطالعاتی

اهداف راهبردی در دستیابی به تجدّد در ایران از دیروز تا امروز

اروپائیان در سده های پیش از هجدهم از امکانات فرآهم آمده در دوران انقلاب صنعتی: تسهیلات تردد و امنیت، گسترش روابط فرهنگی، پیشرفت دانش و شناخت آدمی از پیرامون خود، سود جستند. اینان در طول بحثهای طولانی مستقیم و غیر مستقیم و از راه ارتباط نخبگان خویش "اهداف راهبردی" جامعه ای نوین را پخته کرده و آنها را در قالب اعلامیه حقوق بشر، اصول لائیسیته، جدائی دین از حکومت، پرنقش ساختن نقش رسانه ها ... متبلور ساختند. و متفکرین، روشنفکران، صاحبان قلم با سودجوئی از فضای آزادی قلم این مفاهیم را به اعماق جامعه بردند و آنها را همه گیر کردند.

طی قرون نوزده و بیست، این اهداف راهبردی پخته شده شناخته شده و پذیرفته شده سرمشق کارکِرد این جوامع قرار گرفتند و بر اساس آنها "ابزارهای کاربردی" برای رسیدن به اهداف فوق بتدریج، اختراع شده، امتحان شده و عمومیّت یافتند : چون نمادهای قانون اساسی، مجالس قانونگزاری در سطوح ملی و محلّی، رفراندم، سندیکاها، قانونی ساختنِ انجمن ها و احزاب.

جوامع دیگر بتدریج با این تحوّل بزرگ آشنا شدند و هرکدام بر پایۀ گذشته و موقعیّت خویش در مقابل آن موضع گرفتند. ایرانیان از راه مستقیم شناختِ فرهنگِ فرنگ (فرانسه) یا غیر مستقیم قفقاز، هند، مصر و ترکیه با دنیای تازه آشنا شدند. حاصل این آشنائی تدریجی، در حرکت پای گیر نظام مشروطۀ سلطنتی از ١٩٠٦، قانون اساسی متمم ان متبلور شد. پس از این تاریخ، با فراز و نشیب هائی حرکت مدرنیزه شدن ایران ادامه یافت، اگر چه سرعت، مسیر، کیفیت و کمیّت آن تغییر یافت.

در طی این مدت (مراحل آشنائی، بکارگیری، همه گیر شدن) اندیشمندان و نمایندگان تفکرات و جهان بینی های گوناگون ایرانی تلاش در "مدرنیزه" کردن این برخوردها کردند. مردم نیز در مقابل جنبه های عملی این برخورد، خواسته های خویش را چه در زندگی هر روزه و چه از طریق حضور مستقیم یا غیر مستقیم خویش بیان داشتند. در این میان تفکّر در اهداف راهبردی حرکت به سوی تجدّد به گونه ای به رونوشت برداری از ابزارهای سیاسی، اقتصادی، فنّی ... از غرب منتهی شد. اهداف راهبردی حرکت غرب نه حلاجی شد، نه درک شد و نه با موقعیّت و وضعیّت ما تطبیق داده شد.

حاصل آنکه در طی دو سده تلاش، در کش و قوس بالا و پائین رفتن ها و از طریق چند حرکت متبلور، (انقلاب مشروطیت، جنبش ملی شدن نفت، قیام بهمن ١٩٧٩)، جامعۀ ایران نتوانست مسیر مشخص و بالارونده ای را از تجربه های خویش نشان دهد. در یک نگاه سریع ترازنامۀ این حرکت بهیچ وجه پاسخگوی آنهمه تلاش نیست.

چرائی این ترازنامۀ شوربختانه؛ نه چندان مثبت را می توان در فراموشی اصل مهم حرکات اجتماعی دانست :

تفکر، اختراع و همه گیر کردن "اهداف راهبردی تجدد" برای جامعه ایران

٭٭٭

تلاش ما برآنست که از طریق بررسی اندیشه های متفکرین و حرکات و رفتارهای اجتماعی، سیاسی، اقتصادی، فرهنگی ... در طی این دوران، ترازنامه ای از حضور "اهداف راهبردی تجدّد در ایران" نشان دهیم. این ترازنامه را با همتای غربی مقایسه کنیم، تا بتوان بطور اجمال طرحی برای چگونگی تهیّه و همه گیر کردن "اهداف راهبردی" برای ایران امروز را مطرح کنیم.

٢ـ چگونگی این سؤال، چه هر تحقیق با سؤالی آغاز میگردد :

چگونه است که مردمان سرزمین ایران که در سال ١٩٠٦ توانستند فرمان مشروطیت را به امضاء برسانند و یکی از اولین مجالس قانونگزاری جهان را در خارج از دنیای صنعتی برپا دارند (پیش از روسیه، پیش از چین، پیش از کلیه کشورهای اسلامی، هند، کشورهای آفریقائی) و اصل تفکیک سه قوّه را عملاً در قانون اساسی گنجانده و قدرت اجرائی دولت را از نماد سلطنت و قوّه قضائی را از نماد روحانیت جدا سازند، مطبوعات را به رکن چهارم مشروطیت تبدیل کنند، دولت را در مقابل مجلس پاسخ گو سازند، بیکباره در قانون اساسی ١٩٧٩، عملاً و بطور کلی همه دست آوردهای خود را از دست دادند. و قانون اساسی دوّم در ایران، در تحت پوشش کامل "ولایت مطلقه فقیه"قرار گرفت. بگونه ای که انتخاب ریاست قوه قضائیه، فرماندهان امنیّتی و نظامی به گونه ای مستقیم و انتخاب کلیه دست اندرکاران دیگر، با واستگی شورای نگهبان عملاً در دستان ولیّ فقیه متمرکز گشت.

طرح این پرسش که بی گمان ذهن بسیاری از مردم فرهیخته را بخود مشغول داشته است، نه به این گونه و به شکلی مستقیم، بلکه در قالب طرحها و مطالعات گوناگون، مورد تجزیه و تحلیل قرار گرفته است.

روشی که در این طرح مطالعاتی مورد نظر ماست، بیشتر نگاهی است به چگونگی شکل گیری اهداف تجدّد در ایران در دو قرن گذشته، از ابتدای آشنائی ایرانیان با اروپا تا سال ١٩٧٩.

آگاهی لازم را به ابعاد مهم این پرسش داریم، لیک در مدلیزه ساختن یک پدیده بعمد، تعداد ابعاد را کم می کنیم تا بتوانیم به نتایج نسبی و موقتی برسیم و بهتر بنگریم. بی شک می بایست نتیجه این بررسی را با توجه به ابعاد دیگر مطالعه و بررسی، به قالب نسبیت خویش بازگرداند. این ابعاد بطور بسیار خلاصه چنین اند:

- اقتصادی:

. تولید

. مالی

. ساختاری

. تجارت

- سیاست بین المللی، منطقه ای، ملی

- فرهنگی:

. سنت

. مذهب

. تعلیم و تربیت

- "روانی – اجتماعی" : پرخاشگری اجتماعی – تولید و قدرت روانی

- سازماندهی – تولیدی

- ساختار جمعیتی و سیر آن

- رشد صنعتی و فن آوری در جهان و در منطقه

در این بررسی و با محدود کردن دامنه و بعد و عمق این پرسش وسیع چند نکته را در نظر داریم :

١ـ شروع بیداری ایرانیان را حدود سالهای ١٨٠٠ با اولین جنگهای ایران و روسیه قرار می دهیم.

٢ـ مطالعه خود را به ١٩٧٩ و تصویب قانون اساسی دوم ختم میکنیم.

٣ـ به اهداف عمده، objectifs stratégiques می پردازیم و از ورود به جزئیات می پرهیزیم. چون نگاهی از دور به تغییرات بیش از ١٥٠ سال.

٤ـ در این بررسی و برای مشاهدۀ دقیق تر، اهداف عمدۀ تجدّد، سمت و سو و به عمل کشیده شدن آنها، تلاش داریم که از ورود به تفسیر و تعبیر و قضاوت دربارۀ تغییرات سیاسی، نقش افراد، احزاب، گروهها، اوضاع و تغییرات عمده منطقه ای و جهانی خود داری کنیم. گرچه بخوبی واقفیم که همه این عوامل نقش های اساسی در چگونگی شکل گیری تاریخ ما و تاریخ جهان داشته اند.

اما از آنجا که روابط پیچیده و بیشمار همۀ این عوامل نمیتواند، در یک تحقیق جای بگیرد و هرکدام نیازمند مطالعات گوناگون و فراتر دیگری است، تنها در روش ما و در مطالعۀ ما سیر تحول این اهداف مشاهده میگردند. چون مطالعه در اهداف عمدۀ کارخانۀ تولید اتوموبیل طی یک قرن، بی گمان در تولید اتوموبیل های گوناگون در طی یک قرن کارگران، مهندسان، مدیران و نیروهای متخصص انسانی نقش اساسی را بازی کرده و شرایط زندگی و تاریخ منطقه در کار روزانه آنان تأثیر داشته است. بی گمان حرکات عمده سیاسی، اقتصادی، اختراعات و اکتشافات، پیشرفت علم و فن پردازی، در شکل گیری مدل های گوناگون اتوموبیل مؤثر بوده اند. بی گمان بالا و پائین زندگی زمامداران، مشکلات اقتصادی، بحران های بازار و بالا و پائین رفتن ارزش نفت و انرژی، ... در تولید نقش اساسی داشته است ولی ورای همه این متغیّرها و جدا از همه این عوامل، می توان به سیر تغییر محصولی این کارخانه که همان اتوموبیل است پرداخت و به آنها نگاهی از دید اهداف راه بردی انداخته و مثلاً این سؤال را پاسخ داد که چگونه کارخانه ای که هدف اولیه اش ساختن اتوموبیل برای خانواده های متوسط بوده است، در یک قرن بعد تنها اتوموبیل های گران قیمت تولید می کند و بیشتر به تولید اتوموبیل پاکیزه می پردازد.

به گونه ای دیگر در بررسی ما، اهداف راه بروی تجدّد چون محصول تولیدی همان کارخانه و جامعۀ ایران چون کارخانه فرض شده اند. این نگاه تنها می تواند ما را متوجه فرایند تازه ای کند، که از آن پرسشهای اساسی تر در زمینه های جامعه شناختی، روان شناسی اجتماعی، اقتصادی، توسعه، توسعه فرهنگی و اقتصادی بیرون آید.

تذکر این نکته پیش از شروع ارائه بحث بسیار مهم است که دوستان برای ساعتی، خود را مقید به این کنند که قضاوتها و علائق و تفسیرها و تعبیرهای خود را در زمینه های سیاسی و ایدئولوژیکی به حالت خواب موقت درآورند و پس از نتیجه گیری این بحث اگر آن را مفید یافتند، به نقد دقیق بینش پر ارزش خود بکشانند و همگان را مستفیذ کنند.

به گونه ای دیگر روش ما چون معماری است که به یک بنای تاریخی می نگرد. برای درک چرائی انتخاب ها در برپائی یک بنای تاریخی از تمامی داده های ممکن سود می جوئیم. نقشه های گوناکون بنای تاریخی را تهیّه میکنیم، کاربردها و کارکردها را دوباره بررسی می کنیم. با توجه به موقعیّت زمان و مکان و داده های فنی، نیازها و امکانات تلاش می کنیم اهداف اساسی از ساخته شدن بنا، اهداف کاربردی، شاخص های موفقیّت و یا عدم موفقیّت چگونگی اجرای بنا، مشکلات احتمالی و خطاهای ممکن را بیرون آورده و از این راه، از گذشته چراغی برای راه آینده بسازیم.

٣ـ تعریف تجدّد – modernity- modernité - گرفتاری طولانی تولید می کند که مشکل می توان از چنگ آن خلاص شد.

• آیا تجدّد رونوشت مطابق اصل جوامع اروپائی – آمریکائی است چنانکه : ما باید از نوک پا تا فرق سر فرنگی شویم. این تجدّد معادل مفاهیم westernalization, occidentalisation است.

- آیا تجدّد، اصول بنیائی لائیسیته، سکولاریسم، جدائی دین از دولت است؟ میدانیم که این تعریف کافی نیست چه در بسیاری از جوامع اصولاً دین در جامعه نقش کمرنگی دارد و بهرحال بشکل طبیعی از دولت جداست.

- آیا تجدّد، توسعه افتصادی و گسترش فرهنگی، رفاه فردی است که آنها را با واحدهای اندازه گیری می توان سنجید و امروز خوشبختانه شاخص های فراوانی چه بوسیله سازمانهای بین المللی، بویژه سازمان ملل و یا بانک های بین المللی یا سازمانهای غیر دولتی وجود دارد که کم و بیش موقعیّت جوامع را از این نظر چه با خود آن جوامع در طول زمان و چه مقایسه بین جوامع روشن می کند.

- آیا تجدّد، اجرای هر چه بیشتر و بنیانی اعلامیه جهانی حقوق بشر است؟ در این پرسش نیز ابعاد گوناگون این اعلامیه نمیتوانند برای همه جوامع از اهمیّت یکسانی برخوردار باشند و جنبه نسبی اجرای مفّاد گوناگون این اعلامیه در جوامع گوناگون و اعصار مختلف نمیتواند از یک اهمیّت برخوردار باشد.

- آیا تجدّد، نمادینه شدن "دولت – ملت" در یک فضای جغرافیائی فرهنگی است، با برسمیت شناختن شهروند با حقوق ویژه و الزامات ویژه.

باز هم برای ساده تر کردن بحث و سرعت بخشیدن به آن در مطالعه خود تعریف قابل لمس و قابل اندازه گیری زیر را پیشنهاد می کنیم :

• حضور دولت – ملت با مرزهای شناخته شده و امن شناخت شهروند و حقوق اولیه او.

- حداقل سلامتی جسمی و روانی

- حداقل دسترسی به فرهنگ و آموزش

- حداقل پوشش و غذا و مسکن

- حداقل رعایت ارزشهای فرهنگی و شیوۀ زندگی

- حداقل عدالت و داوری مستقل و بی طرف در رابطه بین شهروندان، شهروندان و دولت

یکی از تعاریف رایج "مدرنیته" در دنیای شرکتهای خصوصی و علم سازماندهی و بازاریابی، همان تعریف بسیار ساده و قابل لمس: مدرن یعنی آنچه که "مُد" است و آنچه که مردم بدنبال آن می روند. آنچه که تازگی دارد و مورد استقبال قرار می گیرد، جای خویش را باز کرده است. اگر بپذیریم که امروزه مردم جهان، آرزوی زندگی مرفّه، سلامتی نسبی، استفاده از آب لوله کشی، برق، امکانات آموزشی و تفریحی، در فضای امن، با امکان دسترسی به رشد اقتصادی – اجتماعی و سیستم قضاوت عادلانه ای را دارند، چندان راه غلطی نپیموده ایم.

٤ـ نگاهی به اهداف استراتژیکِ تجدد:

اهداف استراتژیک (راهبردی)، و تشخیص و شناخت و تعیین آنها در هر زمینه ای کاری است سهل و ممتنع که امروزه در مرز میان علم و هنر و تجربه قرار دارد. شناخت اهداف استراتژیک هم نیاز به شناخت دقیق جزئیات در ابعاد گوناگون تأثیرگذار بر میدان عملکرد این اهداف دارد و هم نیازمند قدرت فوق العادۀ خود رها کردن از دام این جزئیات و پرواز و اوج گرفتن و آینده نگری است. واژۀ استراتژ که در زبان یونانی بمعنی ژنرال و فرمانده نظامی بوده است، امروز در سطح وسیعی و در محدوده های سیاسی، نظامی، صنعتی، اقتصاد ... بکار میرود.

در بیان اهداف عمدۀ تجدّد و تمایلات گوناگون مردم ایران و متفکرین ما از بدو آشنائی ما با این پدیده، مکاتب و گرایشهای گوناگونی شکل گرفته اند. این مکاتب در گویش های مردمی خود را براحتی نشان می دهند:

- ما باید از کف پا تا به فرق سر فرنگی شویم.

- می بایست به اصل خود رجوع کنیم

- تنها راه اتحاد مسلمانان در مقابل یورش "دیگران" است

- باید به دوباره سازی ایران بزرگ بازگشت و احیای زبان فارسی و ...

- تنها راه تجدّد از راه سازندگی و تولید کار و رونق اقتصادی می گذرد

- تنها راه آموزش است و رشد فرهنگ

گروهی نیز در مقابل اختلاف بزرگ و حفره عمیق عدم توسعه و کشورهای توسعه یافته به افسردگی فلسفی و اجتماعی دچار شده اند و می شوند. و یا اساساً باور خود را در قالب : «نسل ما نسلی است (dégénéré) و این فرصت کوتاه زندگی را به خودت برس» از دست می دهند. و یا همان عبارت نقل شده از طرف یکی از پادشاهان قاجار پس از بازگشت از سفر فرنگ را آویزۀ گوش می کنند: «اگر آنها به جلو رفته اند ... ما هم عقب نرفته ایم.» به گونه ای دیگر، آنچه که از اهداف استراتژیک دو قرن گذشته در مورد حرکت جامعۀ خود در ذهن باقی می ماند در چهارچوبهای زیر خلاصه می شوند:

- رونوشت برداری تمام و کمال از غرب

- بازگشت به خود و استفاده از آنچه که هستیم. (هویت گرائی)

- به هر گونه و بهر حال ما باخته ایم و کار از دست ما خارج است و هیچ درمانی نیست و از همه بدتر دچار تئوری توطئه دائم هستیم

- بکارگیری مدلهای موفق دیگر در راه تجدّد

در این میان به سراغ یکی از اسناد معتبر جنبش مشروطه خواهی و تجدد، که همان کتاب "یک کلمه" مستشار الدوله برویم که در سال ١٨٧١ نوشته شده است و بعنوان یکی از منابع اصلی روشنگری و حرکت انقلاب مشروطه شناخته می شود.

بطور اجمال مستشارالدوله، راز و رمز تجدّد را در داشتن قانون، نوشتن و توزیع و اجرای آن می داند. و با مقایسه قانون اساسی فرانسه با مفاد قرآن و اصول سلطنت، جای جایِ کتاب، همۀ این سه مبنا را همآهنگ می خواند. راز نجات جامعه و پیشرفت را نیز در همین یک کلمه میداند، قانون. پیش از بررسی یکایک ١٩ اصلی را که بقول او اصول "کبیره و اساسیّه" در توضیح مختصری، مستشارالدوله در مورد قانون اساسی فرانسه می نویسد: «... چندی اوقات خود را به تحقیق اصول قوانین فرانسه صرف کرده و بعد از تدقیق و تعمق همۀ آنها را بمصداق "لا رحب و لا یا بس الا فی کتاب مبین" با قرآن مجید مطابق یافتم. وی سپس به گونه ای به "روح دائمی کودها" که به گمان ما همان، اهداف استراتژیک یا پایه ای قانون اساسی اشاره می کند و آنها را در نوزده ماده خلاصه می نماید واضافه می کند: «اگر ما تجسس و تفحّص در اجرای کودهای فرانسه بکنیم اطناب بی منتها و کار بیهوده و بیحاصل است زیر که قوانین دنیویّه برای زمان و مکان و حال است و فروع آن غیر بر قرار است یعنی فروع آنها قابل التغییر است.» بطور خلاصه مستشارالدوله که چنان مجذوب "قانون" است، از یکسوی آنها را بعنوان "مدل" و "الگو" می داند و فروع آن را قابل تغییر می شمرد. می توان استنباط کرد، که او به مفهوم اهداف استراتژیک آشنائی داشته است.

قانون اساسی مشروطیت و متمم آن، چندان دور از همان ١٩ اصل مورد نظر مستشارالدوله نرفتند، و اگر چه در مذاکرات مجلس اجتماعیون – عامیون گاه به مسئله بزرگ مالکان اشاره کردند ولی این مهم مورد توجّه قانون گذار قرار نگرفت. خود اجتماعیون – عامیون نیز در افکار خود تجدید نظر کدند و بقول ملک الشعرا بهار در کتاب تاریخ مختصر احزاب سیاسی ایران:

a) صفحه ٩٧ از مشروطه تا جمهوری – ادوار مجالس قانونگذاری در دوران مشروطیت

«اجتماعیون – عامیون شکل تکامل یافته (شعبۀ ایرانی جمعیت مجاهدین) بودند که در سال ١٣٢٢ قمری در مشهد برپا شده بود. این جمعیت خود شعبه ای از اجتماعیون، عامیون باکو بحساب می آمد. پس از استقرار مشروطیت در نظامنامۀ جمعیت مجاهدین تجدید نظر گردید و خود را اجتماعیون – عامیون نامیدند. با آنکه کمیتۀ مرکزی اجتماعیون در باکو قرار داشت و مرامنامۀ آن می بایست توسط کمیتۀ مرکزی دیکته می گردید، معذلک در برنامه های این جمعیت با برنامه های کمیتۀ مرکزی باکو تفاوتهائی دیده می شود. به نظر می رسد سعی در این شده است که مسائل حساس مذهبی و تقسیم املاک را با احتیاط بیان کند، مثلاً برنامۀ باکو درخواست آزادی مذهب نموده ولی در برنامۀ مشهد فقط اشاره شده که هدف مقدّس مجاهدین پیشرفت اسلام است. »

پس از شروع بیداری ایرانیان، بدون شک و با اتفاق نظر مورخان و جامعه شناسان، انقلاب مشروطه را می توان بزرگترین حادثه ای دانست که درهای تجدّد را بر روی ایرانیان گشود و در زندگی اجتماعی مردم ایران تأثیری همه جانبه و عمیق برجای گذاشت.

برای بهتر دیدن، اوضاع ایران و آنهم از دور، چه در اینجا تنها اهداف استراتژیک تجدّد مورد نظر ماست، سه نوع جدول زیر را پیشنهاد می کنیم.

١ـ جدول سیاسی که تنها بذکر تغییرات سیاسی می پردازد

٢ـ جدول عمده تغییرات اجتماعی

٣ـ جدول رسمیّت یافتن عوامل تجدّد – مدرنیزاسیون (توسعه!)

جدول سیاسی ١ جدول ١

فتحعلیشاه پس از آغا محمد خان قاجار به تخت شاهی نشست ١٧٩٧

حملۀ روسها به قفقاز ١٨٠٣

پیمان گلستان ١٨١٣

یورش عباس میرزا ولیعهد به قفقاز ١٨٢٥

پیمان نامۀ ترکمنچای ١٨٢٨

مرگ فتحعلیشاه ١٨٣٤

محمد شاه به سلطنت رسید ١٨٣٤

مرگ محمد شاه ١٨٤٨

شروع سلطنت ناصرالدین شاه ١٨٤٨

سفر اول 5 ماه ١٨٧٣

قتل ناصرالدین شاه توسط میرزا رضای کرمانی ١٨٩٥

سلطنت مظفرالدین شاه ١٨٩٥

مرگ مظفرالدین شاه ١٩٠٦

سلطنت محمد علی شاه ١٩٠٦

محمد علی شاه به سفارت روس پناهنده شد ١٩٠٩

سلطنت احمد شاه ١٩٠٩

سلطنت رضا شاه ١٩٢٥

سلطنت محمد رضا شاه ١٩٤١

٢٢بهمن ١٣٥٧ ١٩٧٩

عمده تغییرات و حرکات و جنبشهای اجتماعی ١ جدول ٢

تحریم تنباکو و لغو امتیاز آن از طرف شاه ١٨٩١

دستگیری میرزا رضا و چند تن از اعضاء حوزۀ بیداران تهران ١٨٩٣

واگذاری انحصار گمرک شمال به مدت 75 سال به روسیه ١٨٩٩

اعتراض بر علیه عین الدوله و باز بودن پیش از حد دست مسیو نوز از مسائل گمرکات ١٩٠٥

اعتراض به ویران کردن گورستان و ساخته شدن بانک استعراضی روسی ١٩٠٥

جنگ روس و ژاپن گران شدن قند، چوب زدن سید هاشم قندی به امر علاء الدوله حاکم تهران، اعتراض آقایان طباطبائی - بهبهانی ١٩٠٥

تحصن در شاه عبدالعظیم: برکناری عین الدوله، علاءالدوله، مسیو نوز، و بنیاد کردن عدالتخانه ١٩٠٥

بست نشینی در سفارت انگلیس ١٩٠٦

امضاء فرمان مشروطیت ١٩٠٦

افتتاح اولین مجلس شورای ملی ١٩٠٦

قانون اساسی با ۵۱ ماده به امضاء مظفرالدین شاه رسید ١٩٠٦

تصویب متمم قانون اساسی (مشروط تصویب پنج مجتهد) ١٩٠٧

به توپ بستن مجلس توسط سیاخوف و به دستور محمد علی شاه و شروع استبداد صغیر ١٩٠٨

ورود قوای روس و انگلیس به ایران

خروج نیروهای روس از ایران ١٩١٧

قرارداد وثوق الدوله (نخست وزیر) با انگلیس و چیرگی اینان بر منابع مالی و نظامی ایران - عدم پذیرش این پیمان توسط احمد شاه ١٩١٩

کودتای سوم اسفند ١٢٩٩ رضا خان ١٩٢١

فرمان کشف حجاب ١٩٣٥

اشغال ایران توسط روس و انگلیس ١٩٤١

غیر قانونی اعلام کردن حزب توده ١٩٤٨

مجلس مؤسسان - افزایش امتیازات شاه ١٩٤٩

کودتای بر علیه دولت مصدق ١٩٥٣

لایحۀ اصلاحی قانون اصلاحات ارضی ١٩٦١

رفراندم ١٩٦٢

دور اول اصلاحات ارضی

دور دوم اصلاحات ارضی

دور سوم اصلاحات ارضی ١٩٦٨

افزایش قیمت نفت ١٩٧٣

٢٢بهمن ١٣٥٧ ١٩٧٩

جدول رسمیت یافتن عوامل تجدد - مدرنیزاسیون جدول ٣

سرهنگ دارسی و شماری از افسران انگلیسی برای تعلیم سپاهیان عباس میرزا به آذربایجان آمدند

اولین چاپخانۀ ایران توسط میرزا زین العابدین تبریزی ١٨٢٢

اولین روزنامه چاپ شد. (کاغذ اخبار newspaper) ١٨٣٧

اولین نقشۀ تهران ١٨٤١

افتتاح دارالفنون ١٨٥٢

افتتاح مریضخانۀ دولتی (چهارصد بیمار) ١٨٥٢

اولین خط تلگراف - میان باغ لاله زار و ساختمان تلگراف خانه ١٨٥٨

تشکیل قوای نظمیه (پلیس) ١٨٧٨

تشکیل قوای قزاق ١٨٧٨

خط تلفن داخل دربار ١٨٨٤

کارخانۀ برق کوچک و محدود ١٨٩٧

کارخانۀ برق تهران ١٩٠٠

ورود سینما و 1903 اولین سالن سینمای عمومی ١٩٠٠

خرید اولین اتوموبیل توسط مظفرالدین شاه ١٩٠٠

مجلس اول: تأسیس بانک ملی - جدائی دین از دولت - مسئولیت دولت در مقابل مجلس ١٩٠٦-١٩٠٨

۱۴دی ماه ۱۳۰۰ تشکیل قشون متحدالشکل ١٩٢١-١٩٤٠

مرزهای مطمئن

از بین رفتن ملوک الطوایفی

وزارت دادگستری

ساختار، راه و پل و راه آهن

نام فامیلی، تبدیل سال شمار به شمسی، بزرگداشت بزرگان علم و هنر و ادب ایران، لباس متحدالشکل

نظارت به اوقاف، برقراری امتحان برای طالبان ورود به حوزۀ علمیه، جدائی دین از دولت

دموکراسی - احزاب - روزنامه ها - گسترش رسانه ها ١٩٤١-١٩٥٢

صنعت مونتاژ - تلویزیون - رادیو - تلفن - جاده ١٩٥٣-١٩٦١

مدارس و بهداشت و خانه عدالت و راه روستائی ١٩٦٢-١٩٦٨

توسعه صنعت وابسته، توسعه دانشگاه و راهها، یکپارچگی نظام شاهنشاهی، عدم دخالت مردم در سیاست ١٩٦٩-١٩٧٦

با بررسی و دقت در این سه جدول مشاهده خواهیم کرد که:

- تا ١٩٢١ نه در عمل و نه در حرف سخنی عمده و جامعی فراتر از مفاد قانون اساسی ١٩٠٦ در مورد تجدّد شنیده نمی شود

- از ١٩٢١ تا ١٩٤١ ؛ نقش "دولت – ملت"، عمده می شود دولت و مرزها امنیت و ارتش، دستگاه اداری و قضائی، آموزش یکسان در شهرها، عمده ساختارها، راه و راه آهن و مسئله برداشتن حجاب و بازگشت آن ولی از حقوق فردی در مقابل آزادی بیان و احزاب و ... خبری نیست

- از ١٩٤١ تا ١٩٥٣؛ یکنواختی اهداف اولیه زمان قبل برای شهرنشینان، بهمراه امکان پیدایش احزاب، نشریات، انجمن ها. افکار گوناگون تجدّد برای اولین بار گسترش تمام می یابد در شهرها.

- از ١٩٥٣ الی ١٩٦٢ ؛ رشد تدریجی تجدّد غیر از مسئله آزادی های سیاسی – اجتماعی در شهرها.

- ١٩٦٢-١٩٦٨؛ اصلاحات ارضی

برای اولین بار اهداف تجدّد به روستاها و کوه و دشت و عشایر میکشاند و دومین حرکت بزرگ را در اجتماع ایران از نظر اهداف تجدّد ایجاد می کند. مالکیت زمین و جنگل و مرتع از دست مالکین، بزرگ مالکین و خوانین بیرون می آید. بتدریج آب لوله کشی، راه روستائی، مدارس روستائی، بهداشت در روستا و بین عشایر مطرح میگردند. با دوران کوتاه و کم رنگ آزادی های سیاسی.

- از ١٩٦٨-١٩٧٨؛ از یکسو سیر مهاجرین روستائی به اطراف شهرهای بزرگ صورت می پذیرد و از سوی دیگر توسعه صنعتی و خانه سازی و راه سازی ... و افزایش دانشگاه و مدارس در شهرها ادامه می یابد دوران کم رنگ آزادی های سیاسی از بین می رود و عملاً نظام شاهنشاهی، حزب واحد رستاخیز و تعبیر مبانی تاریخ به اهداف تجدّد اضافه می شود.

با استفاده از آمارهای ارائه شده در کتاب جغرافیای جمعیت ایران، دکتر جوان، به چند نکته در مورد مهاجرت پس از سالهای ١٩٦٢، از روستا به شهر توجه کنیم. (برای حفظ امانت تاریخها را به همان هجری شمسی که در متن کتاب است، می آوریم).

مشاهده می شود که از نظر مطالعه اهداف "استراتژیک تجدّد" از فاصله سالهای ١٩٠٦ تا ١٩٦٢، دو حادثه و اتفاق و واقعۀ اجتماعی که عمیقاً در زندگی مردم ایران اثر پایه ای گذاشته اند. یکی انقلاب مشروطیت است و دیگری اصلاحات ارضی. هر دو نقل قول از همان کتاب است.

ص ١٢٢ «کاهش جمعیت روستائی در دهۀ ٥٥ـ٤٥ نسبت به ده های ماقبل و مابعد خود بیشتر بوده است به طوریکه اختلاف درصد دهۀ مزبور با دهه های دیگر ٩٫٢ درصد در قبال ٦٫٥، ٧٫٧٢، ٦٫٨ درصد می باشد. در مقابل بیشترین میزان مهاجرت از نواحی روستائی به شهری نیز در همین دهه بوده است. این امر مسلماً بازگو کنندۀ افزایش مهاجرت روستائیان به شهرها در دهۀ ٥٥ـ٤٥ در نتیجۀ تحولات اجتماعی و اقتصادی در سطح کشور بعد از اصلاحات ارضی، ترویج مناسبات سرمایه داری بوده است.»

ص ٣٠٧ «...بدیهی است سرعت شهرنشینی هم بعد از تثبیت وضعیت اصلاحات ارضی و از هم پاشیده شدن ساختار اقتصادی و اجتماعی نواحی روستائی و متعاقب آن جابجائی های جمعیتی شروع می گردد.»

٥ ـ برای اینکه بتوانیم نگاهی دقیق تر بر اهداف استراتژیک تجدد بیاندازیم، تغییرات جمعیتی عامل مهم و بنیانی دیگری را وارد بحث می کنیم.

• طبق آمار در پیش از انقلاب مشروطیّت، ٢٥٪ جمعیت ایران شهرنشین و ٧٥٪ روستائی یاعشایر بودند که از این رقم ٦١٪ به گونه ای یا بروش کوچ نشینی یا نیمه کوچ نشینی زندگی می کردند. به عبارتی دیگر ساکنین امروز ایران با حسابی سرانگشتی با سه یا چهار نسل با درصدی نزدیک به ٧٥٪ به فرهنگی شفاهی، روستائی، عشایری باز میگردند. منابع آمار ارائه شده: جغرافیای جمعیت ایران، تألیف جعفر جوان ١٣٨٠

• به جدول زیر توجه کنید: نمایندگان مجلس، و درصد نمایندگانی که مالک بوده اند، و نیز درصد نمایندگانی که پدرشان مالک بوده است.

• تا ١٩٦٣، از نمایندگان، دهقانان و عشایر و قوانین که بنفع روستائیان بوده است خبری نیست

• در ١٩٥٢، لایحۀ ازدیاد سهم کشاورزان و سازمان کشاورزی، ٢٠ درصد از سهم مالک را گرفته و ١٠ درصد به زارع و ١٠ درصد را به صندوق تعاون (عمران وتعاون) اهداء می کند.

درصد مالکان در مجلس شورای ملی

تاریخ درصد مالکان در مجلس شورای ملی درصد نمایندگانی که پدرشان مالک بوده است

1 ٢تیر ١٢٨٧ - مهر ١٢٨٥ ٢١ ١٨

2 ٣دی ١٢٩٠- ١٠ تیر ١٢٨٨ ٣٠ ٢٩

3 ٢٣آبان ١٢٩٤- ٢٠ اسفند ١٢٩٣ ٤٩ ٣١

4 ٣١خرداد ١٣٠٢ - ١تیر ١٣٠٠ ٤٥ ٣٥

5 ٣٠بهمن ١٣٠٤ - ٢٢بهمن ١٣٠٢ ٤٩ ٤٦

6 ٢٦تیر ١٣٠٧ـ ١٩ تیر ١٣٠٥ ٥٠ ٤٧

7 ١٤آبان ١٣٠٩ـ ١٤مهر ١٣٠٧ ٥٥ ٣٩

8 ٢٤دی ١٣١١ - ٢٤آذر ١٣٠٩ ٥٨ ٤٩

9 ٢٤فروردین ١٣١٤ - ٢٤اسفند ١٣١١ ٥٥ ٤٣

10 ٢٢خرداد ١٣١٦ - ١٥ خرداد ١٣١٤ ٥٣ ٤٢

11 ٢٧شهریور ١٣١٨ - ٢٠شهریور ١٣١٦ ٥٨ ٤٤

12 ٩آبان ١٣٢٠ - ٣آبان ١٣١٨ ٥٨ ٤٤

13 ١آذر ١٣٢٢ - ٢٢آبان ١٣٢٠ ٥٩ ٤٢

14 ٢١اسفند ١٣٢٤ - ٦اسفند ١٣٢٢ ٥٧ ٤٣

15 ٦مرداد ١٣٢٨ - ٣٠تیر ١٣٢٦ ٥٦ ٤٨

16 ٢٩بهمن ١٣٣٠ - ٢٠بهمن ١٣٢٨ ٥٧ ٤٤

17 ٢٨آبان ١٣٣٢ - ٧اردیبهشت ١٣٣١ ٤٩ ٤٢

18 ٢٦فروردین ١٣٣٥ - ٢٧اسفند ١٣٣٢ ٦٠ ٤٦

19 ٢٩خرداد ١٣٣٩ - ١٠خرداد ١٣٣٥ ٤٩ ٥٧

20 ١٩اردیبهشت ١٣٤٠ - ٢اسفند ١٣٣٩ ٥٥ ٦١

21 ١٣مهر ١٣٤٦ - ١٤مهر ١٣٤٢ ١١ ٤٩

22 ٩شهریور ١٣٥٠ - ١٤مهر ١٣٤٦ ٦ ٤٤

23 ١٦شهریور ١٣٥٤ - ٩شهریور ١٣٥٠ ٥ ٣٢

24 ١٦بهمن ١٣٥٧ - ١٧شهریور ١٣٥٤

در ١٩٥٥، قانون سازمان عمرانی کشور از ازدیاد سهم کشاورزان می گوید که در مکانهائی که سهم زارع کمتر از ٥٠ درصد محصول است، ١٠ درصد دیگر از درآمد خالص مالکانه به برزگر می رسد.

• چند نتیجه گیری کوتاه و سریع:

- با وجود تذکر سوسیال دموکراتها : اهداف عمده تجدّد در ایران در سالهای ١٩٠٦ تنها برای ٢٥٪ مردم تهیه شد و بقیه مردم بحساب نیامدند.

- تا سال ١٩٦٢ تغییرات بسیار اندکی در اهداف تجدّد برای اکثریت مردم ایران، ساکنان روستا و عشایر داده شد و مسیر طی شده همان اجرای این اهداف بشکلی نه کلی و معتبر و اساسی، بلکه ناقص ولی برای همان ٢٥ الی ٤٥ درصد بوده است.

- از سال ١٩٦٢ اهداف عمده تجدّد شهرنشینان اجتماعی به مناطق غیر شهرنشین میرسد، بسیار دیر و چون بسیار سریع در فاصلۀ ٦ سال این اهداف صورت می گیرد بسیار عجولانه بشکلی که ساختار کلی تولید یکباره در هم می شکند و اکثریت مردم ایران بدون اینکه جایگزینی داشته باشند به تجدّد هل داده می شوند.

و نتیجه آنکه:

بنیان و ساختار تولیدی اکثریت مردم ایران در فاصلۀ کوتاهی از هم پاشیده می شود.

بعبارت دیگر آنچه می بایست، بتدریج ولی هماهنگ از ١٩٠٦برای کلیه مردم صورت گیرد؛ تا ١٩٦٢ برای اقلیت رخ داد و اکثریت مردم وقتی متوجه شدند که دیگر همه چیز شکسته شده بود

2-

A Look at the Principal Objectives of Modernization in Iran During the Two Last Centuries

Who, in each attempt, will first look and then

Go forward , will make use of his life.

Hafiz, 14th-century Iranian poet

When I asked a famous Iranian historian and social researcher to provide me with a bibliography about the “principal objectives of modernization in Iran during two last centuries”, he responded by saying: “Our cultivation looks like sown fields. Therefore all of our attempts is like this one; we had no strategic objective…”

What Is the Origin of the Question?

How did the Iranians—who managed to establish their own national assembly in 1906, much earlier than most other countries, except those in Europe and North America—completely lose all the beneficial effects of their constitution, which was signed as constitutional patent in 1906, in the constitutional referendum of 1979? These “fruits” were the separation of governing powers—more specifically, the separation of the government and the king’s court, the separation of judicial power from the clerics, and the granting of governmental accountability to the national assembly—and the liberation of the media, which essentially created a fourth power in the country. However, the 1979 constitutional referendum established an “absolute theologian governance” (“Velayate motlagheh Faghih”). According to the new constitution, the Supreme Leader (Vally e Faghih) directly appoints the Minister of Justice, commanders of security forces, and media directors. All other governmental members, such as the national deputies and the President of the Islamic Republic, have to first be approved by the Guardian Council of the Constitution before their election. The Supreme Leader directly, or indirectly through the Minister of Justice, selects the jurists of this council.

Since 1979 the attempt to respond to this question, directly or indirectly, has been the aim of many studies, theses, and articles. Our method here is to focus on the strategic objectives of the two last centuries, from the very onset of the movement that acquainted the Iranian people with the modern world.

Although we are certain that this focus on and modelling of only the main strategic objectives cannot give us a complete answer, we are obligated to choose a limited number of objectives in order to be closer to the real result. The various dimensions that are used in our research are:

- Economical: production, financial, structural, commercial, progress in industrialization

- Political: international, regional, national

- Cultural: religion, education, tradition

- Social and psychological: hope and crises, demographic facts

In our research, we assert the following:

- Iran’s awakening period, provoked by a series of wars with Russia, began in the early 19th century

- The period of our study finishes in 1979, after the institution of the second constitution

- We only focus on the strategic objectives of the modernization in two last centuries; we cannot pay attention to all the details of social, political, regional, and international events

- We try to be objective and do not judge the protagonists: politicians, political parties, and the ideological, historical, or sociological concept. Instead, we try to use the demographic and financial facts, reports, and all the references that might help us answer the questions central to our modeling purposes.

- However, we know that all actions, even the undignified ones, have a place in the historical construction of each society. We can compare our modeling to a great map of a country: Even if we just show the great mountains and rivers, it does not mean that the roads are not important.

The modernization movements in Iran during the two last centuries have been studied by numerous researchers from various fields such as sociology, economics, politics, geopolitics, demography, psycho sociology, and political anthropology. Using well-known theories, they based their studies on the modelling of societal movements: the type of state, the governance, the influence of religion, the impact of tradition, and the cultural bases.

We present here a list of these theories and their conclusions. In brief, the point of our observations is that we did not find a study about the strategic objectives nor their modelling system. Our modelling system needs these following dimensions:

- Economic: production, consumption, exchange, investment

- Development: movement within the different classes of the society and changes to the standard of living

- Cultural: all of the representations of cultural dimensions, such as religion, tradition, knowledge, and know-how

- Organization of society: how the services for the population are produced, how they are evaluated, how they are improved, what is the system of accountability?

- Demographic movement and their origin: population movements and their reasons and impacts

It could be interesting to use an example to better explain the differences of our modelling system versus those of social, economical, and historical studies. For instance, the century-long work-span of a large automobile plant could be modelled by this method. The questions that would be important in our deliberations could include:

- What is produced and for whom, what car models, what are their technical characteristics, and who are the customers?

- How do they build the cars, what are the production processes, what is the cost of a car?

- What is the relation of this unit or factory with the market, according to a study of the movement of capital?

- And finally, how do they prepare for the future of their employees and the modernization of their organization in order to remain competitive?

If the relationship between these elements is harmonious, the activities of the plant can continue and it can be competitive and modern in the long-term future. As it will be observed, that we do not need to know the names of the people responsible nor how many years an individual was the manager. In this analysis, we only need to know how the plant’s strategic objectives changed, why they changed, and what were the effects of these changes. For example, how did the production of the small family car change in the course of a century to the production of the great luxury car?

In our research, we assumed that Iranian society operates like this large plant, and that its product is the civil service that the people receive. Model-building from this point of view may result in new questions that could find their answers in sociological, economical, historical, psychological, cultural, anthropological, and developmental theories. This technique, at least in the beginning, asks experts to try to understand our model before passing judgment. Then, critical questions from the different fields are welcome.

On the other hand, our modelling method uses the same trajectory that an architect uses to understand how an old building lived in its time. The architect tries to draw the plans (after the building’s construction) to understand how the building was designed and constructed, as well as what were the difficulties, mistakes, misconceptions, and theories. By using the strategy map from the Balance Scorecard method, we also try to create broad pictures of the strategic objectives of modernization in Iran across two centuries, mainly by placing all the economic, social, historical, and cultural information about these objectives in the context of geopolitical realities. We know that the documents concerning real reflections about such strategic objectives are rare. For example, a very interesting document named “Yek kalemeh” (“One Word”), written before the Constitutional Revolution, explains that all the problems of Iranian society come from the absence of written “law” (here, “one word” means “law”).

In reality, this research in finding the answer to our main question mentioned above may help us to go even further by trying to find an answer to another important question: “What are the balance sheet results of Iranian society after 1979?” From a strategic point of view, this question is composed of four other questions:

- What are the strategic objectives of the system of the Islamic Republic, and are they achieved?

- What are the strategic objectives of the Iranians, and are they achieved?

- How can we compare the balance sheet of Iran with other countries similar in terms of economical, social, cultural, and geopolitical dimensions?

- And finally, how we can judge these results, where are the weaknesses and strengths in the definitions of these objectives (the system of governance and the people)?

After all, the main objective is to try to construct a country where the people make use of all their opportunities (cultural, natural, geopolitical, etc.) for a better life through the means of modern technology, at least according to the definition of the millennium’s objectives of the United Nations. Such a reflection will enable us to make the past a light for the future.

Definitions of modernity:

The classic definition of modernity by different tendencies can be summarized as:

- Modernity, like Westernization, means to copy and conform to all the principles, acts, and fashions of the West, as the thinkers of modern Iran noted: “We should become Western, from the tail end of the foot up to the head…”

- Modernity means respecting some governance objectives, such as:

o secularism, democracy in a nation-state context

o declaration of universal human rights

o minimum level of comfort and social respect in the use of modern technology

- Modernity, as defined by an enterprising organization, is any opinion that might be accepted by the people in accordance with their perspective of life. This means that if the inhabitants of a country choose to live in harmony with nature by respecting environmental principles, this becomes their definition of modernity, even if other countries continue to abuse nature.

We can conclude that, in the field of our research, modernity from the perspective of Iranian society can be defined as the following:

“Modernity is the respect of secularism, human rights, culture, and history, principles as well as the optimal use of all natural, geopolitical, and cultural potentials. It is to have a secure (externally and internally) nation-state within equated international relations, which can be measured by the indicators of the millennium criterion of the United Nations.”

The Strategic Objectives of Iranian Modernization:

The concept of “strategy” has been borrowed from the military and adapted for business use. In truth, very little adaptation is required as strategy is about means. Moreover, it is about the attainment of ends, not their specification. The specification of ends is a matter of stating those future conditions and circumstances toward which effort is to be devoted until such time as those ends are obtained. Strategy is concerned with how you will achieve your aims, not with what those aims are or ought to be, or how they are established. If strategy has any meaning at all, it is only in relation to some aim or end in view. Strategy is one element in a four-part structure: firstly, the ends to be obtained; secondly, the strategies for obtaining them and the ways in which resources will be deployed; thirdly, tactics or the ways in which resources that have been deployed are actually used or employed; and lastly, the resources themselves, which are the means at our disposal. Thus, together strategy and tactics bridge the gap between ends and means.

Establishing the aims or ends of an enterprise is a matter of policy, which stems from the Greek words politeia and polites (“state” and “people”). Thus, determining the ends of an enterprise is mainly a matter of governance not management and, conversely, achieving them is mostly a matter of management not governance. Those who govern are responsible for seeing to it that the ends of the enterprise are clear to the people who people that enterprise and that these ends are legitimate, ethical, and that they benefit the enterprise and its members.

Understanding these strategic objectives a hundred years after is not easy. It requires a very thorough investigation of various official and international political documents, historians’ essays, speeches by political leaders, and writings by Iranian authors. Rarely can we actually find documents that summarize these objectives, nevertheless naming them as “strategic objectives”. Thus to identify these objectives, we first need to submit all of the dimensions of the event in detail. After placing the information in browsable format, it is possible to find the strategic objectives. Within the language of everyday conversations in Iran about modernization we can familiar hear some ideas. They will help us to have our first schematic impression of these objectives:

- Complete copy of Western culture, organization, and etc.

- Revival of the great Persian origins

- Uniting of all Islamic peoples

- Reconstruction of the country and the opening up of its economic structure, then the rest will change automatically

- Change Iran’s cultural dimension and educational system, then the rest will organize itself

- On the other hand, some intellectuals, when they understood the different standards of living between European and Iranian societies, became greatly pessimistic. They began asserting that the Iranian people, as a race, were degenerated and that it was impossible to find a suitable method for modernization. One of the Ghajar kings, when he heard a lot of talk about the progress and the civilization of other countries after his trip to Europe, reportedly said: “If they have had some progress, it does not mean that we have gone backward...”

- Change the interpretation of all political, social, and humane activities, as well as the theory of conspiracy: “All is decided, arranged, and done by them or by their representatives”. This deep way of thinking greatly influenced the modern political and social thinking of Iran.

- And finally, according to the open-minded intellectuals who believed in a possible path to modernization, Iran should make use of all of their natural and cultural possibilities alongside striving toward technological progress so as to achieve a realistic and happy life for its people. They tried to invent a new procedure more appropriate for society by using the most successful modernization model.

One of the best examples demonstrating the strategic objectives of the Constitutional Revolution was a document named “Yek Kalemh” (“One Word”), which was written by “Mostasharaldoleh” in 1881. This is considered one of the main documents that helped initiate the Iranian enlightenment. The author states that the only way to modernize Iranian society is to have written law (the “one word” referred to in the title) and to use it in all societal activities. In this book, he tried to compare French constitutional law with the verses of the Koran and the monarchic establishment. Ultimately he concluded that there was no contradiction between them and thus, as constitutional law brought modernity to the French, it could also help the Iranians to continue in that direction. In his analysis of the 19 articles of French constitutional law, which he referred to as the “great and basics principles”, he wrote: “I studied the principals of this law for some time and, after deep research and thinking, I find that all of them are confirmed by the glorious Koran.” He went on to explain the “permanent spirit of the articles”: the separation of major and minor articles, distinguishing the major articles, which are permanently correct, from the minor ones that can be changed over time. We can think here that Mostasharaldoleh separated the strategic objectives from the semi-objectives (operational).

The first Iranian Constitutional Law did not go further than the principal articles mentioned by Mostasharaldoleh. Some protests from the “Social-Democrat” faction present in the assembly sought to address the problems related to the large landowners, but they were ignored by the lawmakers. After the Iranian enlightenment in the beginning of 19th century, the Constitutional Revolution was one of the most important events that opened the door of modernization to the Iranian society. It had incredibly important effects on many aspects of Iranian everyday life.

For a better understanding of the events surrounding the strategic objectives of Iran’s modernization after 1906, we will present here three tables:

- The chronology of the political transfer and changes

- The chronology of the social movement and changes

- The important implantations of modernization

Date

The Chronology of Political Transfers and Changes

1797

Fath Ali Shah ascended the Crown.

1803

Assault of the Russian Army on the Caucus.

1813

Pact of non-aggression named Golestan between Russia and Iran.

1825

Assault of Prince Abbas Mirza, the Crown Prince, on the Caucus.

1828

Pact of non-aggression named Torkaman Tchai between Russia and Iran.

1834

Fath Ali Shah died and Mohammad Shah ascended the Crown.

1848

Mohammad Shah died and Nasser al-Din Shah ascended the Crown.

1873

The first trip of the king to Europe.

1896

The king was killed by Mirza Reza Kermani; Mozaffar al-Din Shah ascended the Crown.

1906–1907

Mozaffar al-Din Shah died and Mohammad Ali Shah ascended the Crown.

1909

Mohammad Ali Shah left Iran.

1925

Reza Shah ascended the Crown.

1941

Reza Shah left Iran and Mohammad Reza Shah ascended the Crown.

1979

End of the dynasty of Pahlavi.

Date

Chronology of the Social Movement and Changes

1891

Tobacco protest; concession cancelled by Shah in 1892.

1893

Mirza Reza Kermani and some members of “Bidaran” group were arrested.

1905

In December 1905, two Iranian merchants were punished in Tehran for charging exorbitant prices. They were bastinadoed (a humiliating punishment where the soles of one's feet are caned) in public. An uprising of the merchant class in Tehran ensued, the clergy following suit as a result of the alliance formed in the 1892 Tobacco Rebellion.

The two protesting groups sought sanctuary in a mosque in Tehran, but the government violated this sanctuary and entered the mosque and dispersed the group. This violation of the sanctity of the mosque created an even larger movement, which sought refuge in a shrine outside Tehran. The Shah had no choice, and was forced to agree to the concessions demanded by this larger movement: a "House of Justice".

In a scuffle in early 1906 the government killed a Seyyed (descendant of the prophet Mohammad), and a large number of clergy sought sanctuary in the holy city Qom. Many merchants went to the British embassy for refuge.

1906

In the summer of 1906 approximately 12,000 men camped out in the gardens of the British Embassy. Many gave speeches; many more listened. It is here that the demand for a parliament was born, the goal of which was to limit the power of the Shah. In August 1906, Mozaffar al-Din Shah agreed to allow a parliament and in the fall the first elections were held. In all, 156 members were elected, with an overwhelming majority coming from Tehran and the merchant class.

October 1906 marked the first meeting of parliament, who immediately gave themselves the right to make a constitution, thereby becoming a Constitutional Assembly, and by December 31, 1906, the Shah signed the constitution, modeled primarily from the Belgian Constitution. The Shah was from there on "under the rule of law, and the Crown became a divine gift given to the Shah by the people. Mozaffar al-Din Shah died five days later.

1907

The supplementary fundamental laws of October 7 established the charter of rights and overall system of governance.

1908

Mohammad Ali Shah bombarded the Majles.

1917

On December 15 Russia put in motion its eventual withdrawal from Iran, preparing the way for an indigenous Iranian military.

1919

Iran was coerced to sign a contract with England on August 9, 1919. The terms stipulated in the agreement transferred Iran virtually to the subordinate of the latter.

1921

On February 21 Reza Khan staged a coup together with Seyyed Zia’eddin Tabatabaee.

1935

In 1935, Reza Shah prohibited women from wearing the veil and forced men to wear “Western” dress.

1941

Britain and the USSR invaded Iran to use Iranian railroad lines during World War II. The Shah was forced to abdicate in favor of his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

1949

In1949 the constitutional law was altered so that the authority vested in the Shah was expanded even more.

1953

Coup against Mossadegh.

1962–1971

Significant land reform in Iran took place under the Shah as part of the socio-economic reforms of the White Revolution, begun in 1962, and agreed upon through a public referendum. The land reforms continued from 1962 until 1971 with three distinct phases of land distribution: private, government-owned, and endowed land.

1973–1975

Oil crises brought an enormous windfall to the Shah’s treasury by 1975.

1979

End of the dynasty of Pahlavi

An analysis of these three tables shows that, in the strategic objectives points of view:

- Until 1921, the objective remains the constitution of 1906

- Between 1921 and 1940 the idea of the nation-state become important, along with issues of security. The symbols of modernization, such as education, roads, and railways, become the main objectives, but the respect of human rights is forgotten.

- Between 1941 and 1953 the same objectives are respected for the Iranian citizen (except rural and nomadic populations), while there is some observable progress made in education, sanitation, and industry. Human rights are respected more than before.

- Between 1953 and 1962 the same objectives are seen, but after the coup the respect of human rights lessens

- After 1962, with the land reform and its effects, the strategic objectives of modernization see an important change for the first time since 1906. Modernization is transferred into improving the quality of life as rural civil services, small clinics, and schools come to the rural villages and nomadic life.

- Between 1968 and 1976 there is a mass migration of peasants to the cities. The industrial activities accelerate as the good price of oil helps the Shah establish a strong army. The one-party system is installed; education and a sort of consumer lifestyle is developed in larger cities.

Using statistical information, the effects of migration, and changes in the way of life and production tools, it is obvious that, from a strategic objective perspective, two important social events took place in 1906 and 1962.

As written in the book Population Geography of Iran by Javan:

“The reduction of the rural population between 1966 and 1976 was more than the previous ten years… More importantly, the migration of rural people to the cities also occurred during this time. This is without doubt an effect of the social and economic evolution in the country after the land reform and the establishment of capitalistic economic principles.” p. 122

“Evidently, the rapidity of civilization comes after the land reform and the destruction of the economic and social structure in the rural areas, and the population movements issued from this.” p. 307

For a better interpretation of the strategic objectives of Iran’s modernization, we added the ratio of rural persons, nomads, and city-dwellers into our argumentation:

- Around 1906, the ratio of Iranian society was the following:

o 25% in the cities

o 75% rural and nomadic peoples, of which 61% lived as nomads or semi-nomads

- Even if the power of lawmakers in the national assembly between 1906 and 1962 (the land reform) was not always guaranteed by the political power, a look at the table showing the ratio of landlord deputies to the population shows their prominence during the 20th century in Iran:

Percentage of landlords in the national assembly

Percentage of the sons of landlords in the nation assembly

1

1906–1908

21

18

2

1909–1911

30

29

3

1914–1916

49

31

4

1921–1923

45

35

5

1923–1925

49

46

6

1926–1928

50

47

7

1928–1930

55

39

8

1930–1932

58

49

9

1933–1935

55

43

10

1935–1937

53

42

11

1937–1939

58

44

12

1939–1941

58

44

13

1941–1943

59

42

14

1943–1945

57

43

15

1947–1949

56

48

16

1949–1951

57

44

17

1952–1953

49

42

18

1952–1956

60

46

19

1956–1960

49

57

20

1960–1963

55

61

21

1963–1967

55

49

22

1967–1971

5

44

23

1971–1975

5

32

24

1975–1979

- Before 1963 there were no rural or nomadic deputies in the national assembly, and we cannot find any laws that give importance to their life.

- Meanwhile, two laws passed before 1953 took 20% of the landlords’ holdings for the construction of sanitation systems and roads for the villages. This 20% was reduced rapidly to 7.5% after the 1953 coup.

Conclusion:

- The main strategic objectives of the modernization of Iran before 1962 concerned less than 30% of the population.

- These objectives were not totally respected by the political power.

- The clerical organization, although weak, maintained itself and continued its work due to special taxes and the separate educational system.

- The main strategic objective of modernization arrived very late (after 60 years) in rural areas (more than 70% of the population) and it was executed very rapidly (in six years) without any active participation of the Iranians.

- After 1962, the traditional production system and life structure of rural people were broken. They started to migrate to the cities, where they had many difficulties trying to manage their production and they had no tools to facilitate their adaptation to the new way of life.

- There was a great distance between the strategic objectives of modernization for the people who lived in the cities (about 30% of the population) and the majority of the population in the countryside. This difference helped the clergy to take control of the leadership of the 1979 Revolution.

The main mistake of the strategic objectives in Iranian modernization from 1906 was that the land reform of 1962, which tried to give the humane conditions to the rural and nomad people, should have taken place simultaneously with the Constitution Revolution of 1906 and gradually continue forward, making way for a harmonious society

3- A Look at Strategic Objectives for Iran’s Modernization

4 - Iran Modernization Strategic Map